Among the many significant challenges governments face in the 21st century is the human capital crisis, where there is a struggle to recruit and retain highly qualified employees into the public service. This crisis ties to many other contemporary political issues, from struggles to staff the Trump White House, to attacks on government performance and outsourcing of public services, and even to the graying of America. The famed Brookings Institute and NYU political scientist Paul C. Light sums these trends up best in The New Public Service:

Gone are the days when talented employees would endure hiring delays and a mind-numbing application process to get an entry-level government job. Gone, too, are the days when talented employees would accept slow but steady advancement through towering government bureaucracies in exchange for a thirty-year commitment. In the midst of a growing labor shortage, government is becoming an employer of last resort, one that caters more to the security-craver than the risk-taker.

At the heart of these issues is a core question: why do employees choose the public sector? Or, possibly more importantly, why do employees not choose the public sector?

These are questions that have long interested public officials, political commentators, and academics. Typically, employee motives for choosing jobs are grouped into two categories: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic motivators encourage employees through externally created rewards (i.e., pay or job security) and represent key tools used to recruit, retain, and manage employees. Intrinsic motivators, on the other hand, rely on employees encouraging themselves to work through internally created incentives that are inherent to the job itself (i.e., personal fulfillment). In essence, extrinsically motivated employees work to obtain rewards and intrinsically motivated employees work because of a passion for the job. While organizations use extrinsic motivators to make employment more attractive, intrinsic motivators are part of the job itself and not entirely created by management. As such, no job offers only extrinsic or intrinsic motivators; rather, every job offers a different mixture of these motivators which allows employees to seek out positions that best meets their preferences.

Four decades of research into how the public sector compares to the private and nonprofit sectors, in terms of recruiting and retaining human capital, has yielded two key observations. First, the private sector is the best at providing extrinsic incentives, followed by the public sector and then the nonprofit sector. This pattern exists across a variety of extrinsic motivators, including retirement and health benefits, job security, employer networks, and career advancement opportunities, but is most obvious when it comes to salary differentials.

Second, the opposite pattern exists between these sectors when it comes to intrinsic motivators, with the nonprofit sector being the most adept and the private sector the least. In the public sector, we most commonly refer to this as public service motivation (PSM), where some individuals have a desire to serve the public interest or others that motivates them to public service through psychological incentives. However, intrinsic motivators can be broader than this and include doing “interesting” work, job responsibilities, dedication to organizational missions, or having an impact either on individuals or society as a whole.

For both extrinsic and intrinsic motivators, decades of research tells us that the public sector consistently sits somewhere in the middle between the private and nonprofit sectors, with those sectors providing better opportunities for one set of motivators but not both. These trends are the result of a long-standing cross-sectoral competition for human capital, which has been exacerbated by workforce shortages in highly trained and skilled employees. Traditionally, intrinsic rewards associated with public service delivery were a key public sector strategy for recruitment of highly skilled workers, along with promises of job security and retirement benefits. However, the public service has changed in recent decades with contracting out to private and nonprofit organizations, an emerging social responsibility ethic in business practices, and a growing nonprofit sector. Consequently, public service is now accomplished with cross-sectoral collaboration, where the public sector still maintains leadership but private and nonprofit organizations are highly engaged in delivering public services.

The changing nature of public service has blurred the lines between economic sectors by intermingling public, private, and nonprofit sector missions, and made it easier for employees to balance extrinsic and intrinsic motivators by seeking employers positioned along a continuum that balance their interests. As such, there is increased pressure for all economic sectors to recruit and retain the best and brightest as no sector monopolizes job tasks or functions, and employees choose career paths that may include employment in any economic sector.

EXAMINING THE MOTIVATIONS OF ATTORNEYS

Analyzing trends in employee motives between sectors is difficult as employee responsibilities, backgrounds, and training differ significantly. One profession, however, provides a particularly interesting case to examine. Attorneys make an intriguing and useful case for comparison because educational qualifications and job functions are comparable between sectors, while intrinsic and extrinsic motivators fluctuate widely and attract employees to different types of organizations. To examine these trends, we use data from the first wave of the American Bar Foundation’s After the JD survey, a nationally representative dataset of lawyers in the United States who first passed the bar exam in 2000. We categorized respondents into their economic sector of employment: private, public, and nonprofit. Then, we grouped a series of questions asking respondents about the factors that determined their choice in employment into two constructs: intrinsic and extrinsic. Respondents rated each question on a seven-point scale, from not important at all (1) to extremely important (7). Intrinsic motivators included: substantive interest in a specific field of law; opportunity to develop specific skills; potential to balance work and personal life; and, opportunity to do socially responsible work. Extrinsic motivators included: medium-to-long-term earning potential; salary to pay off law school debts; prestige; and opportunities for mobility.

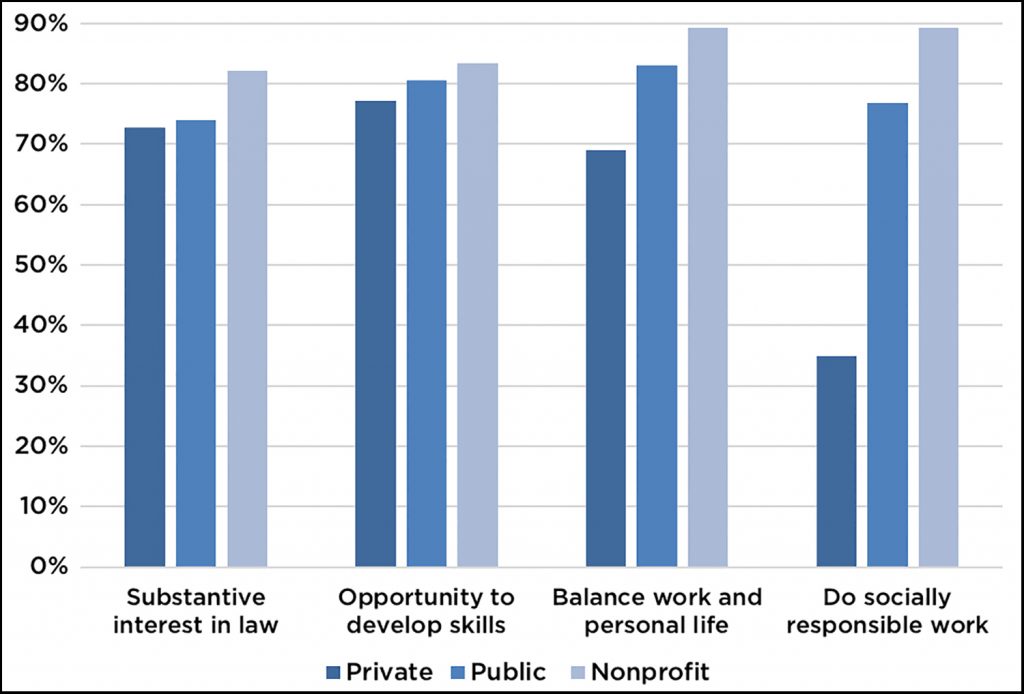

Figure 1 displays percentages of respondents rating importance of intrinsic motivators as a 5, 6, or 7 (i.e., moderately, very, or extremely important). A similar pattern emerges across all four items, where public sector respondents rated items as more important than private sector respondents but not as important as nonprofit sector respondents. The biggest gap between public and private sector respondents and between public and nonprofit sector respondents is for doing socially responsible work. The smallest gap between public and private sector respondents is for substantive interest in the law, and for public and nonprofit sector respondents is opportunities to develop skills.

Figure 1. Responses to Intrinsic Motivator Items

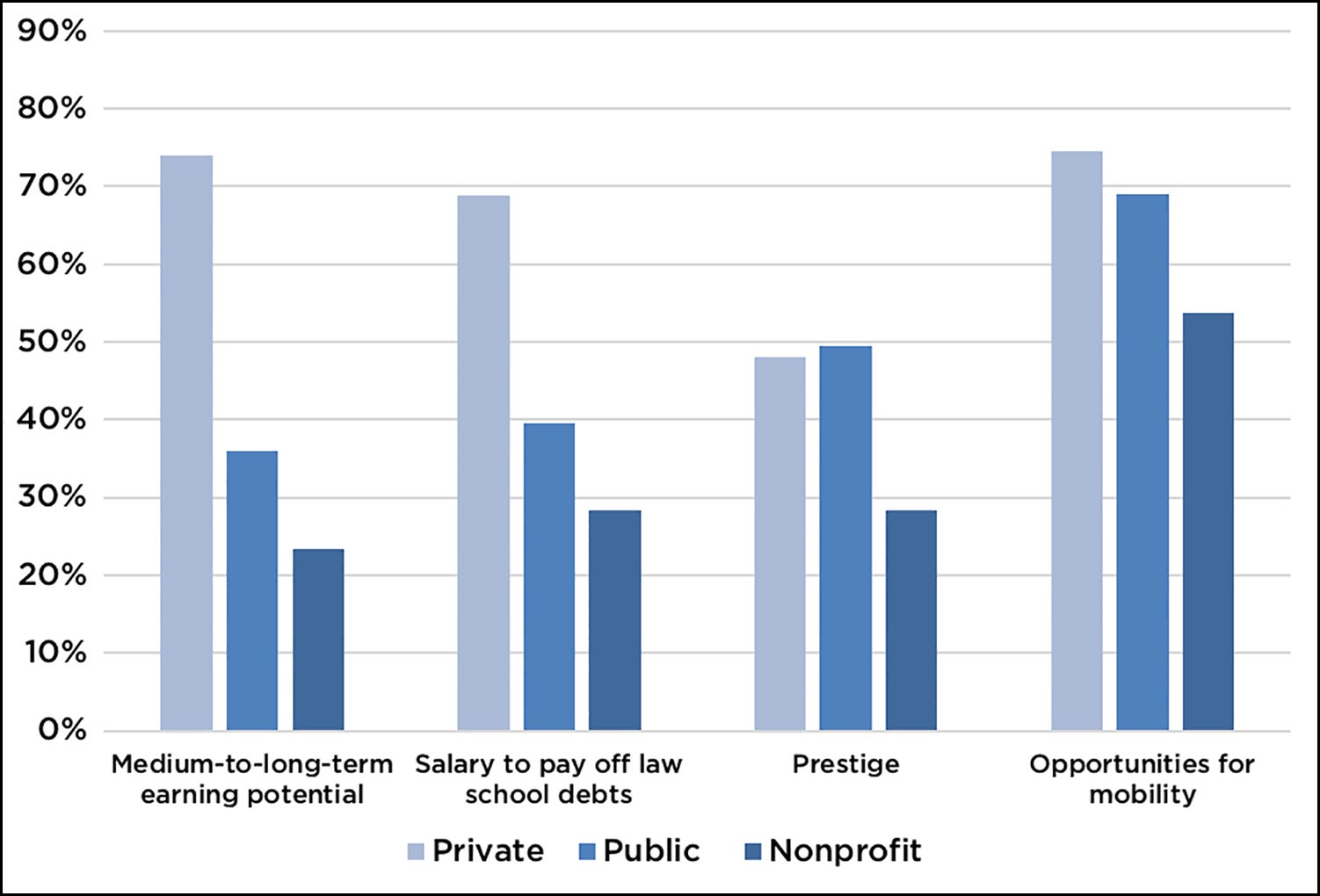

Figure 2 displays percentages of respondents rating importance of extrinsic motivators as a 5, 6, or 7 (i.e., moderately, very, or extremely important). Again, a similar pattern emerges across all four items, where public sector respondents rated items as more important than nonprofit sector respondents but not as important as private sector respondents. The biggest gap between public and private sector respondents is for medium-to-long-term earning potential. On the hand, prestige is the smallest gap between public and private sector respondents and is the only item rated as more important by public sector respondents than private sector respondents. Interestingly, prestige is also the item with the biggest gap between public and nonprofit sector respondents. The smallest gap between public and nonprofit sector respondents is for salary to pay off law school debts. It is worth noting that there appears to be a much larger gap in extrinsic than intrinsic motivators between economic sectors, which suggests many attorneys share intrinsic motives but extrinsic motives are an important point of departure in career decision-making.

Figure 2. Responses to Extrinsic Motivator Items

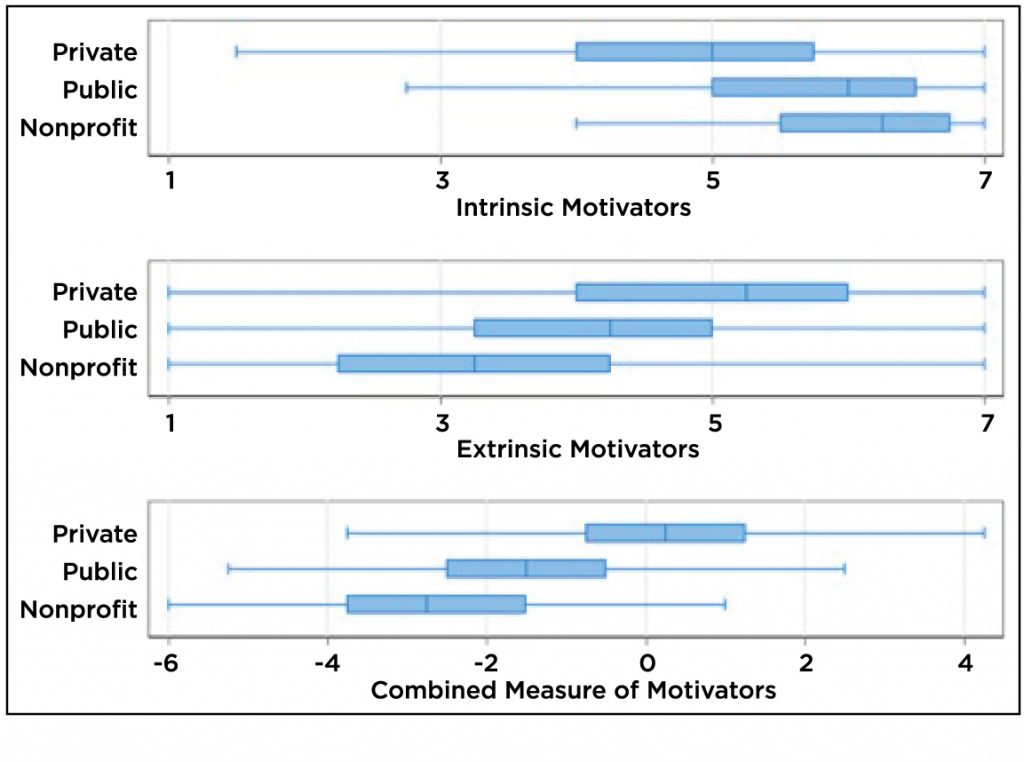

In order to investigate these trends further, we created a single score for intrinsic and extrinsic motivators by taking the averages of items in each category. Additionally, we created a combined measure of motivators by subtracting intrinsic from extrinsic, that ranges from employees completely motivated by intrinsic factors (-7) to those completely motivated by extrinsic factors (+7). These findings are displayed in Figure 3 with box plots. As the box plots indicate, the same patterns emerge here that do in figures 1 and 2, where the public sector is positioned between the private and nonprofit sectors in terms of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivators. The combined measure of motivators in the last box plots highlights this relationship well. Additionally, it is noteworthy that there appears to be much more divergence in extrinsic than intrinsic motivators in the first two box plots, which again suggests extrinsic motivators are an important aspect of career decision-making for attorneys.

Figure 3. Distribution of employee motives across economic sectors

STUCK IN THE MIDDLE OR THE BEST OF BOTH WORLDS?

The public sector faces many significant challenges in the 21st century, and almost all are exacerbated by a human capital crisis where the best and the brightest are no longer choosing to serve their country through employment with federal, state, or local governments. Although public sector jobs were once highly coveted, many employees today find that they can better satisfy their extrinsic or intrinsic motivations through the private or nonprofit sectors, respectively. These trends have been compounded by a shift of public services outside of the public sector, where employees can now provide public services without public employment. As such, the public sector is stuck in between the private and nonprofit sectors, where employees with predominant extrinsic or intrinsic motivations are seeking work in other respective sectors. Consequently, recruiting and retaining human capital in the public sector is more difficult today than ever before.

However, these findings can be seen as an opportunity, rather than another shortcoming of the public sector. For many, public sector employment is the best of both worlds, where they can enjoy good salaries and benefits while serving their communities. Although private and nonprofit sectors may do a good job of providing extrinsic or intrinsic rewards, respectively, neither does as good as the public sector in providing both. For those who want both, the public sector should be their top choice. Unfortunately, that message has been lost in the bureaucracy bashing rhetoric of modern America. Nevertheless, attracting the best and brightest into the public sector can be a solution to many of the challenges of modern governance by creating a high functioning bureaucracy, and a benefit to many employees who want to enjoy both extrinsic and intrinsic rewards from their careers. As such, we need to think deeper about the human capital crisis in the public sector and what it means for both our government and job seekers.

Chris Birdsall is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Administration in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. He completed his PhD in 2016 and his MPP in 2012 at American University in Washington, D.C. Prior to his graduate studies, Chris worked as a Legislative Aide in the Alaska Legislature. His research focuses on public management, performance management, and higher education. He has published in the International Public Management Journal and presented papers at numerous conferences including the annual meetings of the Public Management Research Association, Midwest Political Science Association, American Political Science Association, and Association of Public Policy Analysis and Management.

Chris Birdsall is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Administration in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. He completed his PhD in 2016 and his MPP in 2012 at American University in Washington, D.C. Prior to his graduate studies, Chris worked as a Legislative Aide in the Alaska Legislature. His research focuses on public management, performance management, and higher education. He has published in the International Public Management Journal and presented papers at numerous conferences including the annual meetings of the Public Management Research Association, Midwest Political Science Association, American Political Science Association, and Association of Public Policy Analysis and Management. Luke Fowler is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Administration and MPA Director in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. He completed his Ph.D. at Mississippi State University in 2013. His research interests include policy implementation, energy and environmental policy, state and local government, public management, public budgeting and finance, and organizational theory. He has written articles for American Review of Public Administration, Review of Policy Research, State and Local Government Review, Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting, & Financial Management, Environmental Politics, Social Science Journal, and Electricity Journal. He has also presented papers at numerous conferences including the annual meetings of the Southeastern Conference on Public Administration and American Association of Public Administration.

Luke Fowler is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Administration and MPA Director in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. He completed his Ph.D. at Mississippi State University in 2013. His research interests include policy implementation, energy and environmental policy, state and local government, public management, public budgeting and finance, and organizational theory. He has written articles for American Review of Public Administration, Review of Policy Research, State and Local Government Review, Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting, & Financial Management, Environmental Politics, Social Science Journal, and Electricity Journal. He has also presented papers at numerous conferences including the annual meetings of the Southeastern Conference on Public Administration and American Association of Public Administration.