Marc C. Johnson served as press secretary and chief of staff to Idaho’s only four-term governor Cecil D. Andrus.

In September 2014 Idaho federal district Judge Edward Lodge, a veteran jurist appointed by President George H.W. Bush in 1989, announced that he intended to assume “senior status” in July 2015. Senior status is a type of semi-retirement that allows federal judges to continue to hear cases, but on a much-reduced schedule. By announcing his plans well in advance it was widely assumed that the Obama Administration and the United States Senate would have ample time to nominate and confirm a replacement for Judge Lodge before his senior status began. But this has not happened.

The U.S. Senate may finally consider the president’s nomination of David Nye, an Idaho state district court judge from Pocatello, during the post-presidential election lame duck session of Congress, but even under that best case scenario it will have taken more than two years to fill the Idaho vacancy. Meanwhile, the mounting caseload confronting Idaho’s only other federal judge, B. Lynn Winmill, has prompted the declaration of a “judicial emergency.” This situation represents a dramatic departure from historic norms and it is fair to say nothing like this has happened before in Idaho.

In addition to the Idaho vacancy there are nearly 100 other vacancies in the federal judiciary, including a high profile vacancy on the U.S. Supreme Court. The Senate confirmation process has slowed to a crawl as Republicans and Democrats spar over what many see as an increasingly partisan federal judiciary. Gridlock over judicial appointments appears to have become the new normal in the Senate, but in fact it is a relatively new phenomenon.

Partisans at opposing ends of the political spectrum frequently cite statistics and timelines to buttress claims that the “other side” is responsible for creating conditions that have led to the current political war over the federal judiciary, yet when the partisan talking points are set aside it seems clear that what has gone missing from the current judicial confirmation process is deference to the long accepted belief that in all but the most unusual cases presidential appointments to the federal bench would be confirmed – and quickly so – by the Senate.

Until recently senators in both parties widely accepted as a political reality that the party in control of the White House would be partial – even exclusively so – to judicial candidates who broadly shared the president’s political philosophy. Republican presidents would nominate judges with Republican backgrounds and Democratic presidents would nominate judges who identified with their party. Senators could expect to play a significant role in judicial selections in their states, but rarely by exercising a veto and even more rarely by delaying or denying a confirmation vote.

The traditional etiquette of judicial nominations also anticipated that partisan considerations, while never unimportant, would be tempered by the requirement that the president – any president – nominate prospective judges who are widely respected in their communities, broadly in the mainstream of legal thought and possessed of “judicial temperament.” The idea that a judicial candidate might be held in partisan political limbo for months or even years would have once been seen, by senators of both parties, as an affront to Senate tradition and a degradation of the delicate balance that keeps the federal government working.

The story of a federal judicial vacancy in Idaho more than 50 years ago illustrates how the judicial confirmation process once worked. We know some of the inner working of that appointment because President Lyndon Johnson taped his White House telephone calls. How LBJ went about making a federal judge offers both a mini-study of one president’s decision-making and a striking contrast to how judicial vacancies are handled today.

“HE’S A VERY FINE FELLOW”

At 6:45 pm on the evening of April 1, 1964, a White House telephone operator pushed the intercom button and told President Lyndon Johnson that Idaho Senator Frank Church was on the line. Johnson, certainly one of the most “hands on” American presidents, wanted to talk to Church as part of his due diligence on an Orofino, Idaho attorney he was about to nominate to the federal bench. Johnson almost certainly had on his desk a one-page letter dated November 14, 1963 from Attorney General Robert Kennedy that detailed the background of the attorney and the fact that “he bears an excellent reputation as to character and integrity, has judicial temperament, as is, I believe, worthy of appointment.”

“I’ve got a letter directed to Judge Clark accepting his resignation,” Johnson told the Idaho Democratic senator, “and a suggestion that we name a fellow named McNichols to succeed him. What do you know about him?’

Church knew a great deal about both the incumbent federal judge – Chase Clark was his father-in-law and a Franklin Roosevelt judicial appointee in 1943 – and about Ray McNichols, a close personal friend and loyal worker in the state Democratic Party vineyard.

“He’s a very fine fellow,” Church told the president. “I recommend him very highly…his appointment would be very popular.” Johnson next sought confirmation that McNichols was a good Democrat. “He’s our party?” Johnson asked. “Yes, indeed,” Church said, “And he’s active in the party and well respected for a long, long time.”

McNichols was an active Democrat who had supported Church’s successful campaign for the Senate in 1956 and served as vice chairman of the state’s delegation to the 1960 Democratic convention. Like Church, McNichols had been partial to the candidacy of Massachusetts Sen. John Kennedy in 1960, but Church was quiet on that detail. As the senior Democrat in Idaho, Church enjoyed the senatorial prerogative of recommending a judicial candidate to the president, and McNichols was his man.

Church reminded Johnson that a not infrequent Idaho Democratic kingmaker of that period, Tom Boise, was also a strong supporter of McNichols’ appointment. Boise, a powerful behind-the-scenes presence in the state’s Democratic politics for more than 30 years, had been a Johnson man in 1960. Johnson asked Church to have Tom Boise call him since, as the president said, “I owe him something, don’t you think so?”

Less than an hour later another call from an Idahoan was put through to the president of the United States, and an obviously delighted Boise, a Lewiston resident, confirmed that “this man is your judge,” as Johnson put it. “You be damn sure he’s a Johnson man,” the president said to laughter. “Because he’ll impanel those grand jurors, and he’ll try those cases, and we don’t want anybody who won’t stay hitched.” Boise assured Johnson that McNichols was a man “you can count on.”

“You look after Idaho for me,” Johnson told Boise before adding, “I’m always thankful for friendships like yours.”

Fifteen days later the White House sent Ray McNichols’ nomination to the federal district court of Idaho to the United States Senate. On April 30, 1964, despite the polarizing Senate filibuster over the Civil Rights Act, a debate that split the Senate more along regional than partisan lines, the appointment was confirmed by a voice vote. The next day in Boise, McNichols was sworn in to begin a tenure marked by frequent bipartisan praise for his judicial fairness and common sense. Exactly one month had transpired between Johnson’s phone calls to Church and Boise and the seating of a new federal judge.

MIDNIGHT JUDGES

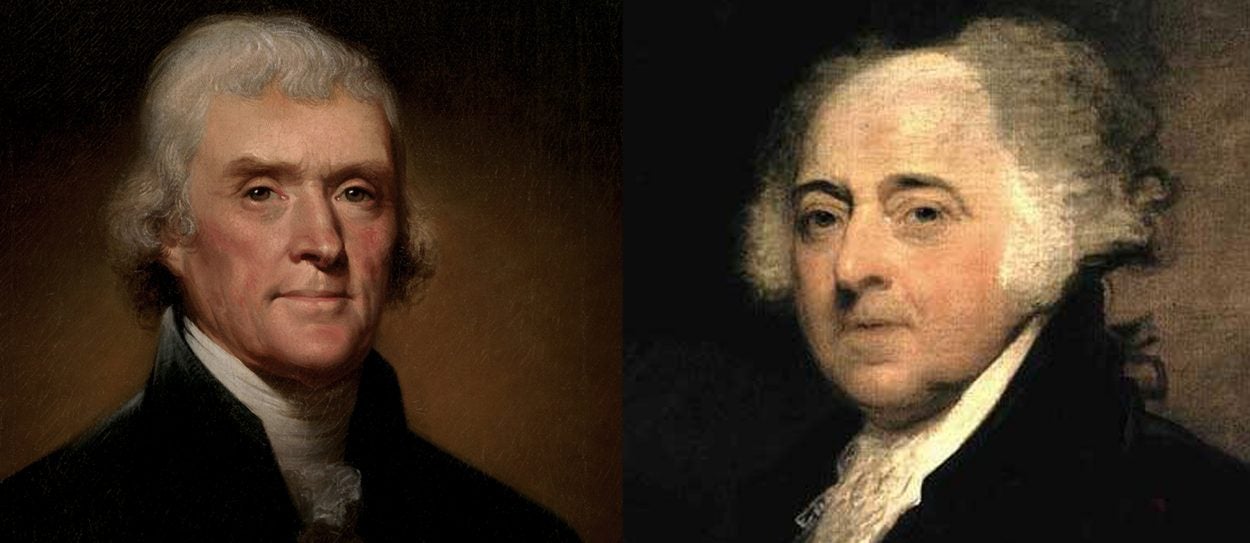

The nomination and confirmation of federal judges has always involved partisan politics. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, for example, dueled over a slate of “midnight judges” Adams jammed through in the dying hours of his presidency. High profile confirmation battles became more frequent in the 20th Century, but a president’s appointment power was widely respected and throughout the nation’s history, with some notable exceptions, the judicial confirmation process has worked to produce candidates broadly in the mainstream of legal thought.

In Federalist 76 Alexander Hamilton argued in favor of the president’s appointment power, convinced, as he put it, that “the sole and undivided responsibility of one man will naturally beget a livelier sense of duty and a more exact regard to reputation.”

Hamilton also advocated a role for the Senate to “advise and consent” on presidential selections as a check against unwise or ill-considered appointments. Yet, in the main, the Founders’ expectation was that the appointment and confirmation process would function even in the midst of partisan division, thanks to the “independent and public-spirited men” (and now women) in the Senate who would consider and with rare exception approve a president’s nominees in the spirit of the greater public good.

But that long-time consensus has now disappeared as the current Idaho judicial vacancy illustrates. Carl W. Tobias, the Williams Professor of Law at the University of Richmond Law School and a close observer of the political battles over judicial confirmation, says the slow down in confirming judicial appointees has steadily worsened as partisan polarization has increased in the Senate. The speed with which a Ray McNichols was appointed in 1964 was “fairly typical as late as the George H.W. Bush Administration,” Tobias said, but such rapid and bipartisan consideration is now virtually unthinkable.

Russell Wheeler, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former deputy director of the National Judicial Center, tracks judicial vacancies. He says “the real victims of this, is not presidents or anyone else, it’s litigants and judges who are siting” on huge backlogs of pending cases. Both Wheeler and Tobias are pessimistic that the gridlock can be broken any time soon due to the poisoned partisan atmosphere in the Senate and the wholesale abandonment of the bipartisan rules that long governed the judicial confirmation process.

A RETURN TO HISTORICAL NORMS?

Does Lyndon Johnson’s speedy and widely-applauded appointment of Ray McNichols more than 50 years ago offer clues as to how the White House and the Senate might return to a judicial appointment and confirmation process that is more in keeping with historical norms? Perhaps.

McNichols, a University of Idaho law school graduate, was not only well known and widely respected by Idahoans active in both political parties, he was well regarded within the state bar. It was also widely known that Church, the state’s senior Democrat, strongly favored his appointment. The appointment process was transparent, and the lack of secrecy eliminated jockeying for the position. Johnson relied on the evaluation of the American Bar Association, which deemed McNichols qualified, and it’s clear from Robert Kennedy’s letter that the Justice Department vetted McNichols with some care, and also with considerable speed.

Boise attorney Neil McFeeley made a study of Johnson’s judicial appointments and he concludes in his book on the subject that LBJ often was very involved in the appointment process, as the McNichols example demonstrates. While Johnson certainly emphasized political considerations, he also sought candidates widely seen as accomplished and independent.

While Lyndon Johnson was capable of making a mistake with an appointment – the Senate refused in 1968, amid charges of conflict of interest, to confirm his nomination of Justice Abe Fortas to become chief justice, for example – Johnson’s approach to judicial appointments clearly worked in McNichols’ case.

After handling more than 2,000 cases during his career, including a landmark anti-trust case involving IBM, a high profile political corruption prosecution of the then-Mayor of San Francisco and the complex litigation resulting from the massive Santa Barbara oil spill of the early 1970s, McNichols was honored by the nation’s trial lawyers in 1984 as the outstanding trial judge in the nation. Following McNichols’ death in 1985 then Republican U.S. Senator James A. McClure called him one of the finest men to ever sit on the federal bench.

The appointment and confirmation of federal judges is steeped in politics, just as Hamilton and the founders knew it would be. Still, the appointment of Ray McNichols by a Democratic president in 1964, a process strongly influenced by Idaho and national political considerations, indicates that a consensus appointee equipped with the qualities of judicial temperament and sterling personal character can be more than a mere political appointee and can indeed become a great federal judge.

Barring a bipartisan return to the once-accepted Senate etiquette surrounding federal judicial nominations, a development that few observers of the current judicial gridlock believe will happen any time soon, it is entirely possible that an appointment like that of Judge McNichols will become a quaint footnote in the history of the federal courts, while a two-year wait to fill a judicial vacancy will become the new standard.