Todd Shallat, Ph.D., is professor emeritus of history and urban studies at Boise State University.

Mistie Rose and Molly Humphreys contributed to this essay.

The Great Pandemic of 1918 spread through a fatal cough. Vomiting and delirium followed. Victims spat blood, then suffocated. Most died within 24 hours.

Known as the Spanish flu — elsewhere as the Spanish Lady, the Blue Death, the Fever of War, and the Great Influenza — the terror hit Boise at the vulnerable, fatal moment of America’s triumph at the close of the First World War. Boise, by then a city of 19,000, had streetcars, opera houses, a Gothic cathedral, and a Moorish spa, but no reliable system of medical reporting. Mysteries continue to cloud the way deaths were recorded. Quarantines, mostly voluntary, were loosely enforced. Only graves and a few brittle public records hint at the murderous toll.

ORIGINS OF THE PANDEMIC

The killer may have originated in China as a lethal strain of H1N1 influenza. Or it may have begun as bird or swine flu in Kansas, where the pandemic was first diagnosed. Shifting and drifting with genetic mutation, the influenza devastated the killing fields of Europe at the close of the First World War. By October 1918 it had swept the globe from France to New Zealand. By February 1919, when suddenly the phantom vanished, the wartime epidemic had killed more soldiers than died under enemy fire.

Epidemiologists have estimated that a third of the Earth’s population may have been exposed to the airborne infection. Perhaps 1 in every 200 people died after exposure.

Wartime suspicion clouded every aspect of the great pandemic. How did it kill? Where was it born? Cures were also elusive. Doctors worldwide were slow to acknowledge the devastation. The Red Cross could do little more than provide surgical masks to swaddle faces in cotton gauze.

About this Essay

This essay, by Todd Shallat, with Mistie Rose and Molly Humphreys, is excerpted, in part, from The Other Idahoans: Forgotten Stories of the Boise Valley, Investigate Boise Community Research Series, Vol. 7 (Boise State University School of Public Service, 2016).

Doctors in Idaho were as dumbfounded as any. “I myself came down with the disease in January 1919,” said Leonard J. Arrington, a historian raised in Twin Falls. “Every hamlet was stricken,” he continued. “Every neighborhood lost children, parents and grandparents. Almost everyone old enough to have memories of it recalls with the grief the passing of a relative, a friend a respected official.”

Sadly, few records exist for Ada County. In 1919, when the U.S. Surgeon General conducted an influenza census, Boise was outside its scope. In 1920, Ada was one of 22 Idaho counties that frustrated health officials by failing to tally and carefully label causes of death by infectious disease.

Perhaps the worst of the fever bypassed Boise. Or perhaps in the Boise Valley, where nostalgia clouded misfortune, the trauma was subconsciously blocked for a city’s self-preservation. Perhaps it called into question the fables of frontier progress with memories too horrific not to repress.

BODIES STACKED LIKE CORDWOOD

Was it meningitis? Bacterial pneumonia? A plot hatched by Germany’s Bayer aspirin? A virus launched from a U-boat?

Europeans first scapegoated Spain because Spanish newspapers had been quick to report the story. But it was an epidemic like no other. Tamer strains of viral influenza had long been common in Europe, hitting mostly the poor, the very old and the very young. But the 1918 pandemic was more democratic. It crippled men as powerful as FDR and President Woodrow Wilson, and the virus hit young adults especially hard.

Scientists still debate why the flu became so deadly. Not until 2004 were microbiologists able to isolate the murderous H1N1 strain. Some say the virus, born in China, had been transmitted through the wartime migrants who labored behind British lines. Some say the fatal strain had mutated in the filth of field hospitals and troop ships. Others say the influenza was American born.

The killer, whatever its source, savaged the United States in three murderous waves: the first, in the early spring of 1918, the second, in the fall of 1918, and the third, in the winter of 1918-1919. “Patient zero” was said to have been Albert Gitchell, an army cook from Kansas, the first to be diagnosed. On the morning of March 11, 1918, at Camp Funston in Ft. Riley, Kansas, Gitchell had staggered into the infirmary with a fever of 103°F. By midday the camp was flooded with 107 cases. By month’s end, the number of cases had surged to 1,127. Forty-eight victims died.

Doctors at first shrugged it off as germs spread by dust storms. In September 1918, however, when the virus jumped to New England, the pandemic could not be ignored. U.S. Surgeon General Victor Vaughan reported the trauma from Camp Devens outside of Boston on the day 63 soldiers died. “The faces soon wear a bluish cast,” said Vaughan, reporting the horror. “A distressing cough brings up the blood stained sputum. In the morning the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cordwood.” Doctors were entirely helpless. Vaughan feared that the killer might murder every human on Earth.

Death toll estimates vary. The U.S. Department of Health has estimated that 165,000 Americans died of the influenza. Ghana in West Africa may have lost 100,000 people; Brazil, 300,000; Japan, 390,000. Worldwide estimates range from 20 to 100 million. The influenza killed more people in 24 months than HIV-AIDS has killed in 35 years.

IDAHO AND THE BOISE VALLEY

“When your head is blazing, burning / And your brain within is turning / Into buttermilk from churning / It’s the Flu,” wrote a poet in Idaho Falls. “When your stomach grows uneasy / quaking, querulous, and queasy / All dyspeptic and diseasy / It’s the Flu.”

But Boise doctors remained unconcerned through the summer of 1918. Dr. William Brady, the Statesman’s medical columnist, predicted the virus would be no worse than others that regularly crossed the Atlantic. “Avoid worry,” said another physician. Westerners were said to be hardy enough to stand tall against influenza. And people who lived in cities, it was said, had resistance to diseases spread in a crowd. Fresh air and exercise were recommended. A Boise Rexall prescribed a flu regimen of iron pills, hydrogen peroxide, antiseptic gargle and cod liver oil.

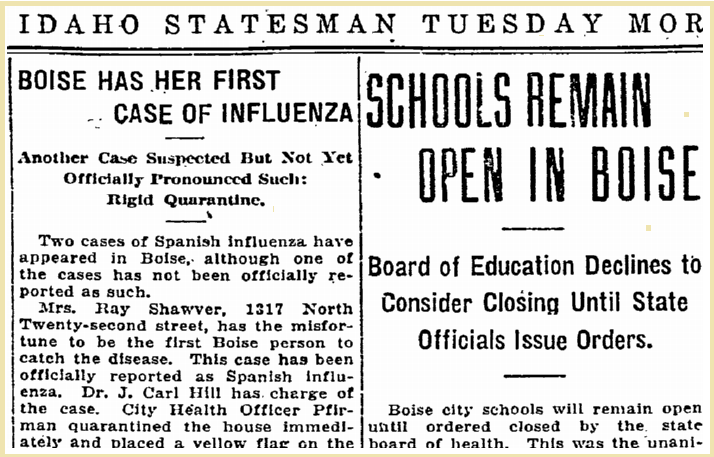

Tunnel vision on the war in Europe kept the disease from Boise’s headlines. “FRENCH TROOPS HOLD OFF HUNS” was the Statesman headline on October 2, 1918, when the killer struck Caldwell and Star. Fifteen people from six families had visited with an infected friend from Missouri. All were quarantined after reporting dangerous symptoms. Olive Michel Shawver of N. 22nd Street had the sad misfortune of being the City of Boise’s first reported victim. On October 15, she was confined to her North End home.

By mid-October the mayor of Boise had joined the Red Cross and the U.S. Public Health Service to ban meetings in public places, closing churches, theaters, pool halls, dance halls, courtrooms, cigar shops and funeral homes. Boise schools mostly stayed open. In Kimberly, Idaho, nevertheless, city officials refused to let Boise-bound travelers step off the train. Deputies in Custer County guarded the mountain passes, arresting travelers or turning them back at gunpoint.

Idaho’s Native Americans grieved some of the pandemic’s worst devastation. In 1918, of the 4,200 natives in Idaho, there were 650 documented cases of flu. Seventy-five died from flu-related heart failure and suffocation. In Nez Perce, a town of about 600 on the tribe’s reservation, health officials estimated 300 cases.

Mormon communities received aid from Utah when the third wave materialized. The city of Paris in Bear Lake County may have lost as many as 500 people — a mortality rate of 50 percent.

Boise, meanwhile, was ill-equipped as any Western city. Boise’s Red Cross offered $75 (per month, presumably) and all travel expenses to lure experienced nurses. Gloves on their hands, gauze on their faces, the nurses delivered hot meals from sanitary community kitchens. Trolley conductors with police power had orders to prevent passengers from spitting or placing their feet on the seats.

Tunnel vision on the war in Europe continued to dominate Boise headlines through October of 1918 as Germany capitulated. On November 11, 1918, Armistice Day, Boiseans flooded the Idaho Statehouse to hear Governor Moses Alexander proclaim the United States’ moment of triumph. A parade — fever-be-dammed — erupted on Boise’s Main Street. “Ten thousand yelling, shooting, screeching, tooting, routing, laughing, talking citizens of Boise parade the streets,” the Statesman reported. A band played “Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight.” A small boy milked laughs with a sign: “The Kaiser has got the flu. He has flown.” The flu, aside from that sign, seemed to be largely forgotten. No health department official dared to stop the celebration. The Statesman reported that only one Boisean at the victory party had worn a surgical mask.

No one remembers whether or not the parade spread the infection. Medical records are sketchy. Brigham Young University has since compiled a “death index” of Idaho fatalities. From October through February, 1918-1919, the index reports 279 deaths in Boise. Influenza or flu is listed as the cause of death in 75 of those cases, more than half of them young adults. Flu-like pneumonia is listed as a cause of death in 60 additional cases.

But if Boise followed the pattern of other American cities, the pandemic of 1918 was dangerously underreported. Hospitals often refused to admit what seemed to be mild cases. And because the virus came in waves with ever-more deadly mutations, there was no standard diagnostic test.

Local resentment of state officials may have also blurred the reporting. On October 20, 1918, for example, state health officials denounced “unpatriotic” physicians who refused to keep careful statistics. One of the accused was Dr. George Collister, the founder of a subdivision. Officials alleged that Collister had failed to quarantine 32 Basques in their Grove Street rooming house. In 1920, the state’s Department of Public Welfare reported in frustration that half of Idaho’s counties had refused to fill out reports.

And then, inexplicably, the virus subsided. In January 1919, even as influenza rebounded elsewhere, state legislators returned to Boise to ratify the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the sale and consumption of demonic alcohol. Theaters had already reopened and, on January 19, the Statesman headlined “SCHOOLS FREE OF DISEASE.” Boise flu cases had fallen below 600. By February the phantom was gone.

GRAVE MISFORTUNES

No memorial recalls Boise’s pandemic — none but the granite in the cemeteries, marking the victims in rows. Boise’s cemetery at Morris Hill inters at least 110 bodies from the wartime virus. Laborers, housekeepers, nurses, cooks, janitors and railroad workers — they were local victims of global misfortune, more than half of them young adults.

Agnes Stites was one. Age 22 when she died in 1918, Stites had suffocated while spitting blood at St. Alphonsus Hospital. Her flu-stricken baby daughter, age 22 months, died the following day.

Ystora Yoshihara of Japan, another victim of influenza, was a naturalized citizen who worked as a cook at the OK Restaurant on Boise’s Main Street. Influenza took him at age 41.

Albert P. Smith of Boise, age 50, died from influenza and heartbreak just four days after the death of his teenage daughter, Thelma Louise. He had been a boiler inspector in the Eastman Building. She had worked as a stenographer.

Edward Jeff Brummett, a farmer, had relocated from New Mexico with his wife and children about six months before his death by influenza at St. Luke’s Hospital. His wife also died of the influenza. He was 28. She was 20. Their daughter and son took sick but survived.

What these unfortunates had in common was bad timing, mostly. Bad timing had made them too young for immunities from past pandemics, too old to benefit from coming advances in medical science that brought virus vaccines. Bad timing moreover had brought these victims to Boise at the fluke tragic moment when 12,000 Idaho troops had returned from Europe in shock and jubilation, spewing disease.

A century later it remains our own sad modern misfortune to write about common people in an era of celebrity wealth. “Sad stories are a hard sell in Boise,” says Bruce DeLaney, the owner of a downtown bookshop. Only the headstones are left to recall forgotten pandemics, marking memories collectively lost.