Todd Shallat with Amber Beierle

Todd Shallat with Amber Beierle

Todd Shallat, Ph.D., is Professor Emeritus of History and Urban Studies at Boise State University. Amber Beiere, M.A., is the author of Old Idaho Penitentiary (2014) and Idaho’s administrator of historic sites.

A sandstone cellblock under Boise’s Table Rock Mesa laid bare the in-between shadowy nature of the female felon’s mercurial place. If biology was destiny, if the fairer sex was God’s favored gender in the progress of civilization, then what was the woman who strayed?

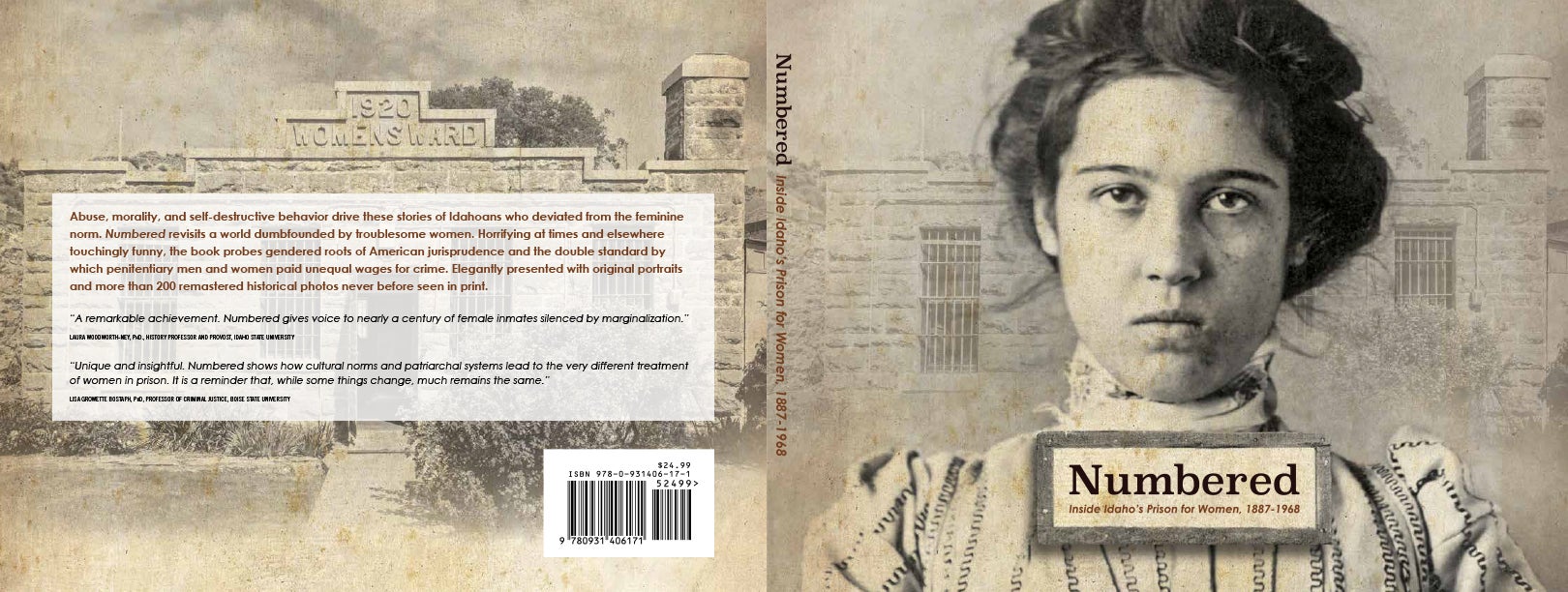

Prison was once the end of the road for only the most desperate and troublesome Idaho women. From 1887 to 1968, in the turreted penitentiary at the eastern edge of Idaho’s capital city, 216 women were numbered and mugshot as involuntary wards of the state. Nearly all shared a stout little sandstone cellblock in the shadow of the male prison. The Women’s Ward, it was called. Seven tiny double-occupancy cells opened into a concrete dayroom. Built with convict labor, its stone cut from the quarry a mile east of the site, the ward stood 18 feet by 20 feet, behind a 17-foot outer wall. No guard tower commanded the cellblock. No buzzers or bulletproof glass.

“Our ward is rather small,” wrote inmate Nancy “Chris” Christopher in 1960. Three years earlier, she had used chairs and a table to scale the garden’s perimeter wall.

So few were the crimes, so frequent the pardons, that the solid little cellhouse stood nearly empty at times. Thirteen months was the average sentence. Five days was the shortest. Nineteen years, the longest. Six inmates were the most admitted in any one year before the crime wave of the Great Depression. By 1965, however, the Women’s Ward had overcrowded, and health officials began to demand that the cellblock be permanently closed.

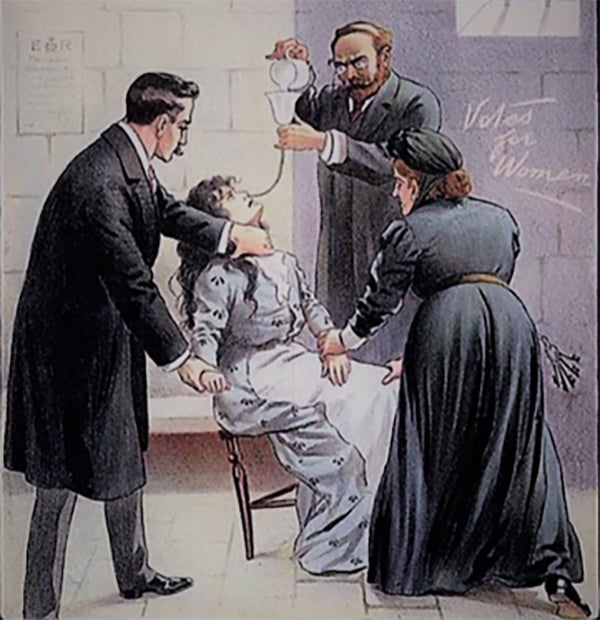

Women had been an afterthought to the criminal justice system on the eve of Idaho statehood. Susan B. Anthony, the suffragette, an inspiration to Protestant temperance ladies in Boise and Pocatello, stressed rote biology that turned men into violent offenders and women as morally fit to vote. For men, said Anthony in the 1880s, the motive for crime was “love of vice.” For women, it was “destitution.” A woman, unlike a man, could be morally rehabilitated. Idealized, she was a flower too frail for back-breaking physical labor, too submissive for public floggings, too pious and pure and timid to commit the most heinous of crimes.

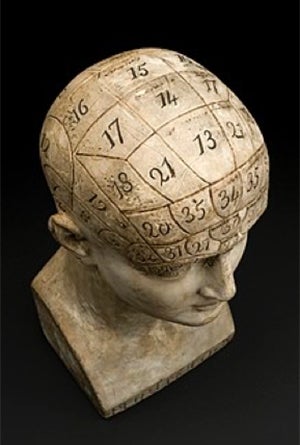

But what of the transient, the paupered, the battered, the broken, the inebriated, and the drug addicted—the women who fell short of social expectations, too depraved to be held for years on end in the county jails? Criminologists at the University of Turin searched for answers by pricking convicts with needles and reading the bumps on their heads.

Cesare Lombroso’s La Donna Delinquente (1893) – a key example of the era’s scientific racism and sexism – theorized that the female offender was an “atavistic” throwback to a more primitive breed of apelike humanoid creatures. Their small craniums with sloping foreheads marked their congenital defects. So did jutting jaws, jug ears, hawk noses, colorblindness, and numbness to pain. Prostitutes were likely obese, according to this Darwinian “science.” Deviants, often left-handed, were prone to epilepsy. Female killers had a glassy stare in their bloodshot eyes.

But Lombroso’s theory was hard to square with the Idaho women living under Table Rock Mesa. French, Mexican, Nez Perce, Swedish, Irish, Mormon, and Baptist, they were a jumble more diverse than the state’s population. The shortest was 4 feet 9 inches, the tallest 5 feet 11 inches, the smallest 93 pounds, the largest 240 pounds.

Multiracial and multilingual, they were “organisms responding and reacting to various [environmental] stimuli,” said the criminologist Frances Kellor, writing in 1901. Kellor considered head bumps incidental to the mind-bending power of capitalism’s social decay. Physical abuse, sexual exploitation, poor education, low wages, and the tedium of menial jobs were said to be preconditions of female criminal recidivism. Alcohol and narcotics also bred criminal lives.

To Kellor goes much of the credit for coining “underclass” as a word to explain the toxic symbiosis of poverty, minority status, and poor education that became the common social markers of life on the bottom rail. Low wages for tedious work, an important predictor according to Kellor, was one of the few quantifiable measures of underclass status in Idaho’s inmate files. From 1908 to 1968, of the Women’s Ward’s 211 inmates, four out of five were listed as housekeeper, housewife, or “unknown.”

There were also waitresses (36 inmates), cooks (9), nurses (9), farm laborers (5), clerks (3), bar maids (3), a beautician, and a potato sorter. Sixty-seven inmate files linked delinquency to vagrancy or extreme financial distress.

Today, by comparison, the National Institute of Justice has cited poverty and poor education as the strongest predictors of criminal recidivism, characterizing 79 percent of women in prisons and jails.

Race was another factor. Significantly, with only 3 percent of the state’s population listed as nonwhite in Idaho’s mid-century census, 21 percent of the Women’s Ward inmates were categorized as Native American, African American, or Mexican. Among the Native Americans, mostly Shoshone and Nez Perce, the words “drunkenness,” “dope,” and/or “narcotics” appear in 21 of 23 inmate files.

Especially vulnerable were the 60-plus penitentiary women convicted of forging or writing bad checks. Many were single mothers with hungry children—in Pocatello, for example, where French immigrant Sarah Bradley forged checks to feed four children; in Twin Falls, where Ruth Haynes, mother of five, floated checks to cover her disabled son’s hospitalization; in Lewiston, where Lola Hewett promised to make restitution on a $20 grocery check. Credit card fraud ensnared Emily May McLaws, who was offered parole but had nowhere to go. All were women who fit Kellor’s description of “restricted activity” in farm-based economies with few escape routes for unmarried women.

Likewise, it was minor offenses for petty sums that overwhelmed Barbara Singleton, a four-time repeat offender, who listed her occupation as housewife and repeatedly kited checks throughout Twin Falls County. Court documents implicate an abusive husband on probation for the same offense.

Not everyone was impoverished—not the clerk embezzler from a Boise family of standing; not the madam arrested for bootlegging or the deputy county treasurer who skimmed $9,000 to cover her gambling debts. Of the 30 most violent offenders, those convicted of murder or manslaughter after 1906, there were 13 with criminal files that mentioned extreme financial hardship. Another eight were listed as housewives.

Both the rich and the poor won pardons. “This is due to the sympathy and consideration which men give women,” Kellor explained. Five months of a 10-year maximum sentence earned the governor’s pardon for Flossie Phillips of Lincoln County, who, in 1940, had helped her brothers hog-tie their father, leaving him in the desert to die. For Caddie Shupe of Montpelier, convicted of shooting her lover, the promise to return to her husband was quid pro quo for reducing her sentence by half.

For Margaret Brooks of Montana, who tossed her infant from a fast-moving train, a year and a month was enough. Lyda Southard, aka Lady Bluebeard, served about four years per murdered husband. Of Idaho’s 37 women convicted of murder and manslaughter, 1887 to 1968, only five served more than 10 years.

Paroles and pardons seemed to be Idaho’s way of conceding that many a violent offender had been fighting off a drunken man. Jeannette Benoy of Idaho County, age 65, served two-and-a-half years for blasting a boozed-up husband who was beating her with an iron bar. An African American cook from Twin Falls named Mary Turner Hansom sat for her 1936 mugshot with an eye welted shut from a beating. Convicted of killing her husband, Hansom had shot him, she said, “on accident” in an era of victimization about 50 years before battered woman syndrome became a legal defense.

Brawls that sent women to prison usually ended with a smoking handgun. Frances Ernst of Valley County, age 36, had used a pistol to stop dead a fight between a jealous husband and a lusting neighbor. When the husband confessed to the shooting, Ernst emerged from hiding to volunteer her own confession. She appears to have been one of only two women in the sandstone cellblock for its 1920 renovation.

Cells now had steam heat, electric lights, flush toilets, and bunkbeds. There was a whitewashed dayroom with a Victrola and woven rugs but very few inmates. Not until 1937 were more than five women in shared confinement. Not until 1954 did the seven-cell ward reach its double-occupancy cell capacity of 14.

In December 1960 the arrival of a 15th inmate forced a second inmate to sleep in the dayroom. “The more the merrier,” wrote Nancy “Chris” Christopher, reporting for Idaho’s one and only penal publication, a newspaper called The Clock. “What are we going to do if more guests come? There are several of us here who I am sure would be more than glad to relinquish their space to some more deserving person. I suppose, and if necessary, we can always resort to three-tiered bunks.”

Fifteen women with little to do sometimes made time for mischief. A prison hooch called “squawky,” also called raison jack, pruno, or brew, challenged the thirsty to imbibe while holding their noses. Coffee grounds and bread yeast were fermented into foul concoctions.

Another amusing annoyance was the teasing and flashing of men. In 1966 a volleyball game turned raucous when a woman, retrieving a ball, climbed on the roof to yoo-hoo a red-shirted male inmate. A visit from the warden followed. “We don’t like having you here any more than you like being here,” said Warden Louis E. Clapp, a veteran of 22 years. “I wish you would learn to behave like ladies. Ladies don’t get on top of a building and wave.”

But ladylike behavior in the 1960s was not what it was in 1906. Women now sat as judges and jurors, and many were less forgiving than men. Second-wave feminism took on marital rape, unequal pay, and discriminatory custody laws. In 1968, the year the Women’s Ward folded, protesters threatened to burn bras and marched against the Miss America Beauty Pageant. Pop-culture B-movie classics such as So Evil, So Young fetishized the female offender as butch and sadistic.

“Women in prison [are] looked upon as hard and cold as steel,” Christopher explained in The Clock. “The sister is ashamed to be with you. The agency sees you as a woman who has lost the right to be a mother. Then the heartache comes. It is like a giant hammer beating on a molten mass.”

On July 1, 1968, after 62 years, the Women’s Ward officially closed. Four prisoners topped out their time at women’s prisons in Oregon and Nevada. Another generation would pass before Idaho reclaimed its own at the Pocatello Women’s Correctional Center, opened in 1994.

Today, per capita, Idaho ranks fifth in the nation in females incarcerated. The state’s population of female offenders grows at double the rate for men. Looking backward, the contrast is stark. Suspended between then and now, between the eras of the Victrola and iPhone, is the history of separate but decidedly unequal gender treatment by Idaho courts of law. A morality tale, it is the story of a double standard—for women, the strictest purity; for men, the freedom to carouse and indulge.

The history of lives in confinement is also about race and class. Then as now, among men and women, African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics were overrepresented. So were the transient, the paupered, the battered, the broken, the inebriated, and the drug- addicted. Few left behind memoirs or mausoleums. But their lives, if we listen, astonish us. Faintly we can hear them still in their cold confinement where vacant faces in graying mugshots whisper through concrete walls.

Excerpted in part from Numbers: Inside Idaho’s Prison for Women, 1887-1968. Todd Shallat and Amber Beierle, eds. Boise: Idaho State Historical Society, 2020.