Todd Shallat, Ph.D., is professor emeritus of history and urban studies at Boise State University.

Westward, in barren Utah, the course of empire derailed.

“INDIAN TREACHERY,” blasted the 1853 headline. “The most brutal outrage ever committed,” said a broadside from Salt Lake City concerning the killings in Utah’s Kingdom of Zion. But why the mutilation, with legs amputated and arms axed off at the elbow? Where were the corpses? Why had a jury acquitted the killers? Even now, the mystery beguiles.

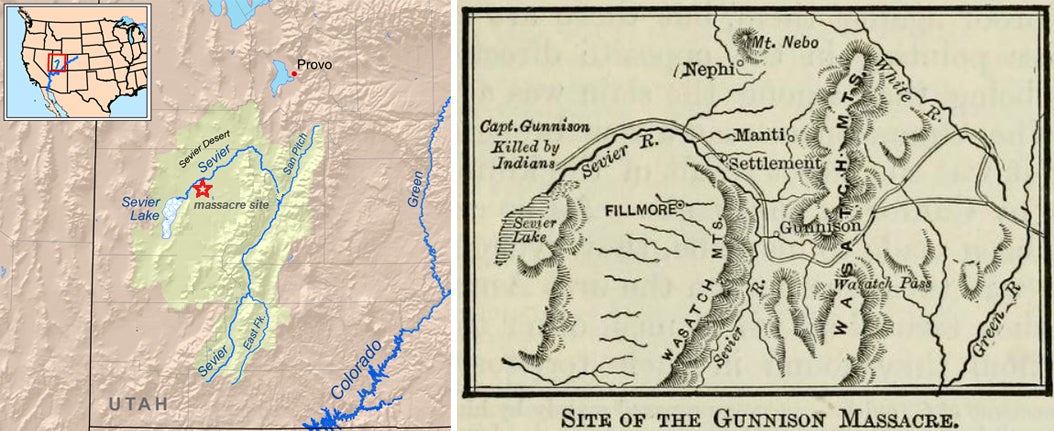

On October 26, 1853, on Utah’s Sevier River, Captain John Williams Gunnison of the U.S. Topographical Engineers had died in a volley of 15 arrows, killed among the carnage of seven men in his command. One trooper escaped by plunging into the river. Another turned as he fled to see Gunnison’s heart being ripped from his chest.

This article is adapted from a longer essay, which includes source documentation.

Pahvant Indians did the killing, perhaps in revenge for the slaying of kin on the gold road to California, perhaps mistaking Gunnison’s crew of army surveyors for the emigrants who shot at the natives for sport. But immediately there were conspiracy theories. Brigham Young of the Latter-Day Saints, Utah’s governor and Mormon prophet, stood accused of a terror campaign to sabotage Gunnison’s plan for a transcontinental railroad. Young, it was said, feared the railroad would corrupt with a flood of nonbelievers; or, in an alternate telling, he wanted the rails turned north through the Valley of the Great Salt Lake.

Another whisper involved the recent unwelcomed publication of Captain Gunnison’s sociological treatise concerning the Latter-day Saints. Young, it was alleged, had the engineer snuffed as payback.

“I have always held myself that the Mormons were the directors of my husband’s murder,” wrote Gunnison’s widow in a petition to a federal judge.

Sadly yes, wrote Judge William Drummond in a scorching letter reprinted in the New York Times. Drummond of Chicago, a presidential appointee, had recently been arrested for assault in Utah. Resigning his judgeship, he fled with an army escort and a theory about Mormon snipers in the willows behind Gunnison’s tent. “The whole affair was a deep and maturely laid plot to murder,” the judge insisted. White men in war paint, he alleged, had signaled the ambush. Corpses had been left to the wolves to hide the bullets in Gunnison’s chest.

It mattered naught that the story was hearsay. Mormondom had become barbaric in the court of public opinion. Debauchery now reigned in Utah, said Democrat Stephen A. Douglas on the floor of the U.S. Senate. Zion had become “a pestiferous cancer . . . a loathsome disgusting ulcer.” The tumor would have to be knifed at its root.

GUNNISON’S GHOST

Suspicion exploded in outrage in the walled city of Nephi at the Gunnison massacre trial. On March 24, 1855, after a miscarriage of justice denounced as a farce and noonday madness, a Mormon jury acquitted all six Pahvant defendants. Three were released. Three others were allowed to escape.

Two years later a new President was in the White House and a federal army of 2,500 was marching on Salt Lake City with orders to depose Brigham Young. Mormons prepared for the worst, burning crops, abandoning farms. To the south near Cedar City, where the Sevier crossed the road to San Bernardino, a caravan of 40 Arkansas wagons rolled west in a thunder of cattle. Mormon militiamen and their Paiute allies waited in ambush. On September 7, 1857, at daybreak in a clearing called Mountain Meadows, sniper fire cut the ear off a child and felled the first seven defenders. After four days of withering siege—their water depleted, their dead decomposing in the baking heat of the wagon enclosure—the defenders agreed to lay down their arms.

Then, in a blink, the unthinkable happened. Under a white flag of truce, as two lines of prisoners walked single file, a militia commander rose in his stirrups and shouted “do your duty!” Point blank, on cue, the captors turned on the captives, clubbing, stabbing, and shooting. One hundred twenty pioneers died, women, men, and children. Coyotes and buzzards scattered their corpses for miles.

Mormon authorities blamed the Paiutes. Newspapers from New York to San Francisco were quick to blame Brigham Young. Again, it was said, the assassins were white men in war paint. Again, it was feared, the vipers would never face trial.

Few academics ever believed it. Hubert H. Bancroft’s History of Utah (1889) said the charges against Governor Young were “groundless,” the rumors “entirely false.” Mormonism, nevertheless, dominated the retelling of Gunnison’s tale as it fused with Mountains Meadows in a two-part epic of horror. Mormon “destroying angels” sneered as they kidnapped and killed in novels by Joaquin Miller (1881), Robert Louis Stevenson (1885), and Zane Grey (1912). Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson matched wits with same avengers in A Study in Scarlet (1887). Mormon outlaws called Danites blackened the silver screen in at least two dozen silent movies. Brigham Young resurfaced as vindictive and violent in Lights and Shadows of Mormonism (1909), The Unsolicited Chronicler (1994) and American Massacre (2003). On Netflix, more recently, where Mormons in caricature are often alien outsiders, the destroyers slap leather in September Dawn (2007), Hell on Wheels (2013), and Godless (2017).

We need massacre stories, it seems, to settle unfinished business. We need things to go bump in the Utah night wherever tragedies need explanation—at Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City, for example, where a memorial to the Battle of Bear River neglects to mention a methodical slaughter of noncombatants; at Ephraim, Birdseye, Pinhook Draw, and Salt Creek Canyon where the massacre markers list only the Christian dead.

Likewise we need Gunnison’s story to prosecute guilt never proven in trial. But here the plotline stumbles. Missing from the murder equation is plausible prophet motive – what had motivated the LDS prophet to orchestrate such sensational mayhem? And missing from the tale in its modern retelling is visceral noir connection to a shadowy sinister place.

ESCALANTE’S MIRAGE

If ever a place was cursed by its melancholy, it was the highest and driest of North American deserts, the largest and least populated, the most disparaged and misunderstood. It was “worthless, valueless, d[amne]d mean God forsaken country,” said a peddler crossing Utah. Mark Twain imagined “a vast, waveless ocean stricken dead and turned to ashes.” For cowboy novelist Owen Wister, writing 1897, the Great Basin of Utah-Nevada was an “abomination of desolation . . . a mean ash-dump landscape . . . lacquered with paltry, unimportant ugliness . . . not a drop of water to a mile of sand.”

It was here some 15,000 years before the present that ancient Lake Bonneville had split the plateau in one of history’s most massive floods. Swirling and crashing north toward the Snake-Columbia drainage, carving chasms, tossing boulders larger than bison, the Bonneville Flood left Utah salted with playa lakebeds. The Great Salt Lake remains the largest with standing water. Second is Sevier Lake in Utah’s Millard County. Its salt crust sparkles crystalline white like 27 miles of snow cones. But Utah still calls it a lake. Google Maps punks boat-towing tourists with a vast blob of digital blue.

The salt-crusted lake that was never a lake realized Columbus’s dream of a northwest passage from Europe to Asia. So said Padre Velez de Escalante, a Spanish Franciscan. In 1776, on a search for Indian souls and golden cities, Escalante had camped about 40 miles east of the lakebed. Perhaps it had recently rained and the sink held standing water. More likely in the distance he saw flats refracted into the blue of a lakelike mirage. That illusion, whatever the source, inspired an era of profound cartographic confusion. Alexander Finley’s Map of North America (1830) showed a freshwater lagoon where the Sevier River became Rio Buenaventura. Mighty and broad, the Buenaventura flowed west, bisecting the Sierra Nevadas. Utah maps of the 1840s still traced a river connection via Sevier Lake to the San Joaquin-Sacramento and San Francisco Bay.

Had the trapper Jedidiah Smith survived to publish his notes on the Sierra Nevadas, the fable of the Northwest Passage might have died a generation before Gunnison met Brigham Young. Instead it remained for the explorer John Charles Fremont to report, in 1844, that the interior was a landlocked “great basin,” its rivers draining inward. There was no Rio Buenaventura, no outlet to San Francisco.

But still there remained on Fremont’s map a triangular void called “unexplored” about the size and shape of New England. Stretched from nowhere to nowhere, from the Wasatch Front to the Mojave through sundrenched shadeless mountains, it was a waste given by God to Mormons because, said Brigham Young, it suited no other people on Earth.

Even so, Congress wanted a map. Was there water enough to sustain a railroad? And where was Escalante’s mirage?

NOWHERE MAN

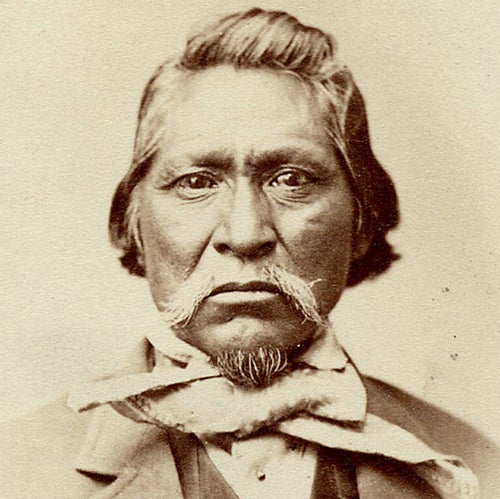

A glass-plate photograph shows Captain J. W. Gunnison, age 40, with a look of crazed foreboding in the blankness of dilated eyes. Wavy hair ducktails west as if dust-blown toward California. A raised eyebrow under the high forehead of a receding hairline gives him the quizzical look of a man too tenaciously single-minded to be sidetracked by an Indian war.

Born in New Hampshire, schooled at West Point, he stood at the vanguard of American science at its golden moment of triumph when the desert, no longer Satanic, became a marvel of romantic fascination. Like John C. Fremont, also a skilled topographical engineer, Gunnison had authored an important book and parlayed political connections into the choicest frontier assignments. Gunnison, of the two, had proven the more able and cautious, having crisscrossed Colorado without once having to admonish his troops for resorting to cannibalism.

In October 1853, however, Gunnison blundered into a war zone. Chief Wakara of the Timpanogos Paiutes, a legend known for beaver hats and theatrical yellow war paint, had broken with Brigham Young over the advance of settlements toward Lake Utah. Wakara’s warriors vowed eye-for-an-eye retaliation for every spilling of Indian blood. Meanwhile, on the fringe of Wakara’s domain near the trade outpost at Fillmore, a clan of Paiutes called Pahvants supplied the wagon migration, trading buckskins for textiles and bread. Tragedy had struck in late September when five visiting Pahvants wandered into an emigrant camp. Panicked, a pioneer drew his revolver. An Indian elder fell mortally wounded. His sons swore revenge.

“There is a war between the Mormons & the Indians,” Gunnison reported from the Sevier River near the hamlet that now bears his name. “Parties of less than a dozen do not dare to travel.” His own party was 12 men exactly. A botanist, a sketch artist, a guide, a cook, a captain, and seven dragoons, they had detached from the 37-man expedition sent west to plot the railroad. “We did not know what a risk we had recently been taking,” wrote Gunnison to his wife in a hasty letter, his last.

Smoke signals tracked the surveyors as they scouted their final campsite in the scrub oak of the ancient delta above Escalante’s mirage. Snow dusted the Pahvant Mountains, an opaque whisper beyond the scrub grass. Waterfowl squawked in the wetlands. The following morning, cold and bright, a rifleman without his rifle staggered back to the camp of the main expedition. Gunnison and seven others were dead.

Of the many storylines that emerged, some blaming Wakara, others Brigham Young, the most plausible was the testimony of the greying Pahvant chieftain who spoke for the assailants who confessed to the crime. Chief Kanosh, a Mormon ally, named the ringleaders as three sons of the elder killed on the wagon trail near Fillmore. Kanosh called them “boys.” In their fury, seeking revenge, the teenagers had heard the gunshots of men hunting geese, located the campfire, assumed in the falling darkness that the hunters were an emigrant party, and returned with a posse of armed companions.

None were Mormons in war paint. A crime of mistaken identity, the ambush was fury misdirected in the dappled October twilight: an attack on unknown travelers in an unexpected location by assailants who could hardly fathom why men might journey 1,000 miles to survey an empty lake.

A KILLER DECEIVES

“It was a time of war,” wrote Brigham Young in the wake of the killings. “It cannot be expected of the Indian, in their present low and ignorant condition, with all their traditions and ferocious natures, to understand and act in accordance with the provisions of law which they never had the least knowledge of, nor any opportunity for obtaining such information.” Custom dictated that the son of a murdered man had a social duty, an obligation, to enforce lethal revenge on the clan of a perpetrator. A Mormon variant of that Paiute doctrine resurfaced at the trial of the militiaman charged for the slaughter at Mountain Meadows. Again it was war, said the defendant. Vengeance justified retribution against members of a rival clan.

If Brigham Young was complicit, it was after the fact in his reluctance to execute allies. If the doctrine of vengeance shares blame, then so, too, did the army that trespassed. So did the commander who selected a vulnerable campsite. So did the vacant strangeness of the Sevier desert itself. Always a West of the imagination, a projection of heartbreak and fear, it was a barren Escalante had called Severo, meaning savage and violent. A passage, a pariah, it was a basin of small pox, anthrax, nuclear fallout, alien sightings, a WWII Japanese American relocation camp, and many dozens of Indian battles—all within a radius of 100 miles.

An enigma for American science, the Sevier killed and deceived. Not until 1872 did a scientist reach the lakebed. Not until 2013 did the Corps of Engineers concede that the second largest lake in Utah lacked water enough for the laws that govern a lake.

Today, along Gunnison’s march to nowhere are highway signs that proclaim “I survived Route 50” and “America’s Loneliest Road.” Stop at the Great Basin Museum in Delta to see the commemorative plaque from the engineer’s vandalized gravesite. Laid to rest in pieces, Gunnison decomposes nearby—his thighbone under granite in the City of Fillmore, his skull, never recovered, in the chalk-white silt of a vanishing delta where a killer’s silent accomplice still haunts the core of the crime.